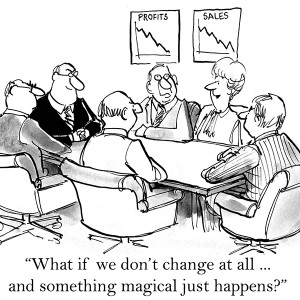

‘Who is your leader?’ Try this question next time you meet a doctor or nurse in the NHS; you’ll be amused by the confusion it causes!

It’s hard to convey the disconnect between the ‘frontline’ of healthcare and the executive of the NHS.

For a start, there is the gap between the day-to-day operations of a hospital and the ‘middle management’. Typically, individual doctors and nurses make clinical decisions about patients. These decisions are almost entirely taken without reference to any formal ‘manager’. For example, whether to operate on a patient, prescribe a particular drug or order a diagostic test. These decisions are ‘clinical’, in the sense that they impact on the direct care of individual patients. But, they are also financial, in that they carry a cost, of which the clinician is almost totally ignorant.

Next, there are the daily, run-of-the-mill operational decisions, such as covering for sick leave and who does what, when and where. These could be described as administration or co-ordination decisions. Low-level functionaries, such as rota co-ordinators or secretaries, frequently make these sorts of decisions. They may have little understanding of the clinical or financial implications of their decisions. For example, they may have learnt that an operating list can accomodate x number of cases, but they won’t have any information or insight into the particular issues of each case (the ‘casemix’), so schedules can be inappropriately light or hopelessly over-ambitious. Idiosyncratic ‘clinic rules’ can be concocted, which are rarely scrutinised by senior managers. This leads to widely differing productivity between clinicians doing the same work.

Middle managers are often experienced nurses, who prefer the regularity of ‘9-5’ posts. They rarely want to set the world on fire with innovation, but rather value stability and predictability. They fear the ire of senior managers so try to keep a tight ship and avoid trouble.

The most to be pitied are the senior managers or directors. These are below the Executive, but are held accountable by the Executive for the poor financial and operational performance of their domains. They may have little training in management or leadership, yet bear heavy responsibility with little power over egotistical and hard-to-replace senior doctors. They spend most of their time fire-fighting and ‘managing up’.

The Executive are frequently remote, both physically and emotionally, from the frontline of the hospital. For fun, I sometimes ask clinical colleagues the names and titles of any of the Executive Board. The rarely know more than one or two, and often none.

So far, we have just stayed within a Trust. But, of course, there are myriad ‘quangos’ with an interest in the performance of a Trust. So, much of the time of Trust executives is spent managing them. NHS Improvement (NHSI), NHS England (NHSE), the CQC and local CCG’s, all concern themselves with the performance metrics of those actually doing the frontline work. However, the hospital’s frontline staff have virtually no interest in, or even awareness of, these ‘overlords’, who have no impact on their daily lives.

Finally, there is the charade of political control. The senior leaders in the ‘Service’ (the name used by politicos in the Department of Health and Social Care for the NHS), are careful to provide ‘evidence’ of how the NHS is constantly improving. So, despite dismal international comparisons and the lived experience of patients and their relatives, the ‘public’ continue to believe that the NHS is the envy of the world!

So, the picture painted here is of ‘meaningless management’. Lots of busy managerial activity almost wholly disengaged from the outputs of the clinical workforce. A mirage of leadership.